At this point, everyone is familiar with the “Uncanny Valley,” the concept of the eerie liminal zone between human and non-human that provokes a primal feeling of unease. Humanoid robots, bad CGI (i.e. The Polar Express), and prosthetic limbs are all common examples of the Uncanny Valley, and the term has also experienced a bit of a renaissance lately with AI-generated images, which are often recognizably life-like but with enough details feeling slightly off to trigger the Uncanny sensation.

While the term itself is ubiquitous, the actual origins of the Uncanny Valley, and its connection to the Freudian concept of the Uncanny, is underexplored territory. Tracing back the roots of Uncanniness over the last century can help illuminate the mechanisms of Uncanniness in the current moment of AI, and I believe provide a key to the broader existential feelings that AI provokes.

Mori

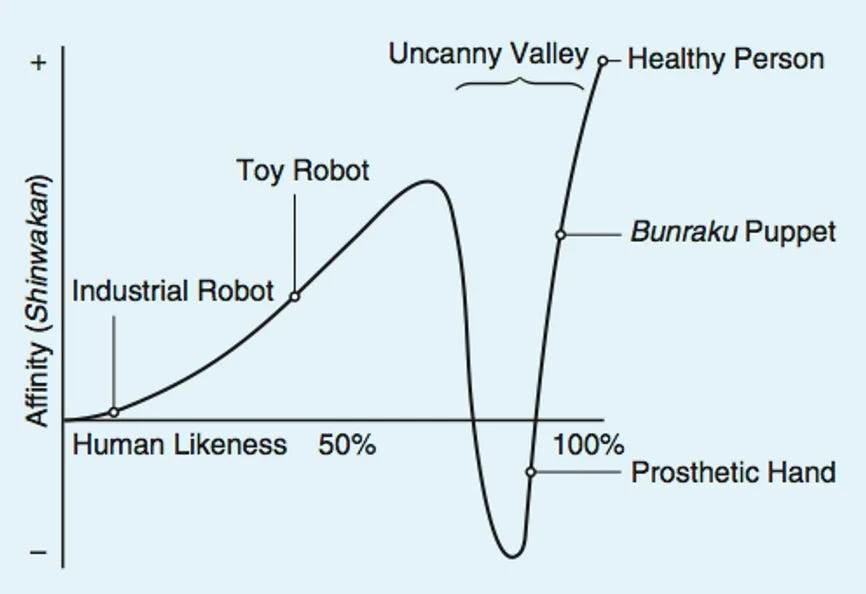

Let’s work our way back from The Uncanny Valley. Written by roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970 for the obscure Japanese journal Energy in 1970, his essay coined the term and outlined the basic principles in two charts, based on the axes of human likeness and affinity (as in, do people feel positively about it).

Mori begins by describing how, typically, industrial robots don’t aim to look human, and are designed for functionality:

“Nowadays, industrial robots are increasingly recognized as the driving force behind reductions in factory personnel. However, as is well known, these robots just extend, contract, and rotate their arms; without faces or legs, they do not look very human. Their design policy is clearly based on functionality.”

Approaching the first peak, he describes toy robots, which are designed with loosely human-like aesthetics in mind, and kids love them. So they’re medium in both likeness and affinity. Mori places Bunraku puppets even higher on the scale of likeness and affinity, just below the very top—a healthy person. The Uncanny Valley exists between these peaks, where likeness is high but affinity is negative—Mori uses the example of a prosthetic hand:

“One might say that the prosthetic hand has achieved a degree of resemblance to the human form, perhaps on a par with false teeth. However, when we realize the hand, which at first sight looked real, is in fact artificial, we experience an eerie sensation. For example, we could be startled during a handshake by its limp boneless grip together with its texture and coldness. When this happens, we lose our sense of affinity, and the hand becomes uncanny.”

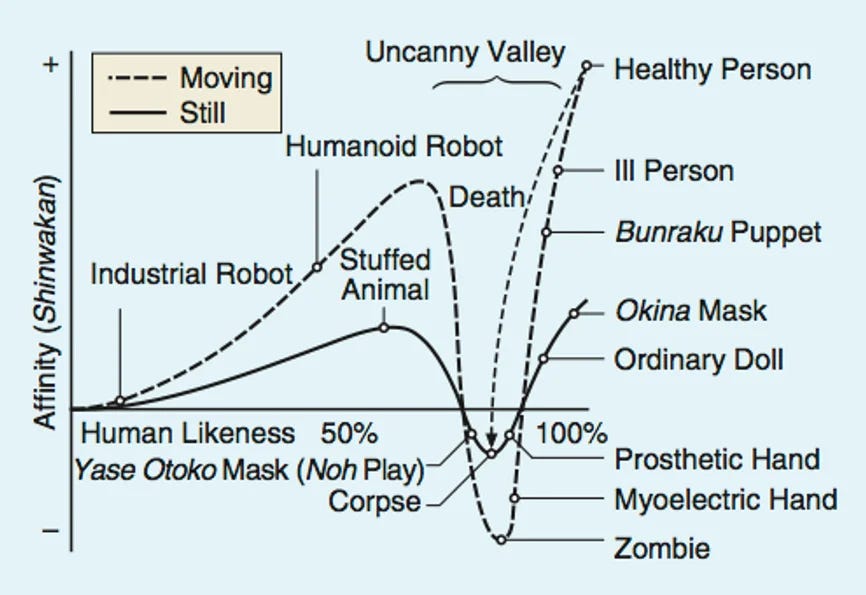

Mori then reveals a new chart, with a second, dotted line. The dotted line factors in movement, and has an even steeper slope. Mori gives the example of the added eeriness of a moving disembodied prosthetic hand, and provides a somewhat fanciful anecdote:

“Imagine a craftsman being awakened suddenly in the dead of night. He searches downstairs for something among a crowd of mannequins in his workshop. If the mannequins started to move, it would be like a horror story.”

Also notable on the second chart is the line that travels backwards, from human (highest affinity) to corpse (Uncanny Valley). Mori explains:

“As healthy persons, we are represented at the crest of the second peak in Figure 2 (moving). Then when we die, we are, of course, unable to move; the body goes cold, and the face becomes pale. Therefore, our death can be regarded as a movement from the second peak (moving) to the bottom of the uncanny valley (still), as indicated by the arrow's path in Figure 2. We might be glad this arrow leads down into the still valley of the corpse and not the valley animated by the living dead!

I think this descent explains the secret lying deep beneath the uncanny valley.”

So, maybe, the secret is death? Let’s keep that in mind as we move back to the roots of the Uncanny in Freud, and even earlier, in Ernest Jentsch.

Jentsch

Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay The Uncanny is a classic piece of psychoanalytic writing, a rare Freudian text that is mostly based around literary analysis, and a popular reference point in the humanities. But Freud’s essay is itself a response to an earlier paper by Ernest Jenstch, On the Psychology of The Uncanny (1906), the first psychological reckoning with the concept. Jentsch’s essay primarily focuses on the Uncanny’s association with “uncertainty,” and it lays an important foundation for Freud’s expansion of the Uncanny. Jentsch draws attention to the linguistic slippage between canny/uncanny (heimlich/unheimlich), situates the Uncanny in a psychological framing, emphasizing the effect rather than the cause; he focuses on the Uncanny in art and namedrops E.T.A. Hoffmann, who Freud will devote a significant portion of his essay to; he speaks of wax figures and panoramas, and even has a bit about movement that sounds very much like Mori’s definition of Uncanny:

“A doll which closes and opens its eyes by itself, or a small automatic toy, will cause no notable sensation of this kind, while on the other hand, for example, the life-size machines that perform complicated tasks, blow trumpets, dance and so forth, very easily give one a feeling of unease. The finer the mechanism and the truer to nature the formal reproduction, the more strongly will the special effect also make its appearance.”

Finally, Jentsch ends on a note similar to Mori’s, again evoking the fear of death that seems to be central to the Uncanny:

“The horror which a dead body (especially a human one), a death’s head, skeletons and similar things cause can also be explained to a great extent by the fact that thoughts of a latent animate state always lie so close to these things.”

Again, death appears to be at the root of the Uncanny, though it’s not yet entirely clear how.

Freud

Freud builds on Jentsch’s foundation of the Uncanny, honing it from the overarching idea of “uncertainty” into a more focused paradigm of interlocking anxieties. His essay is only around 20 pages, but it is highly allusive, sprawling, and sometimes contradictory, so rather than go through it point-by-point, I’m going to try my best to pull out the key points and interpretations.

Like Jentsch, Freud starts with an etymology of heimleich/unheimlich:

“The German word unheimlich is obviously the opposite of heimlich, heimisch, meaning ‘familiar,’ ‘native,’ ‘belonging to the home’; and we are tempted to conclude that what is “uncanny” is frightening precisely because it is not known and familiar. Naturally not everything which is new and unfamiliar is frightening, however; the relation cannot be inverted. We can only say that what is novel can easily become frightening and uncanny; some new things are frightening but not by any means all. Something has to be added to what is novel and unfamiliar to make it uncanny.”

Freud accuses Jentsch of not moving beyond this “uncertain,” then goes into a lengthy section of definitions for heimlich/unheimlich in various languages, and essentially comes the conclusion that the words have a dialectical relationship:

“Thus heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops towards an ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich.”

This linguistic slippage between familiar and unfamiliar is precisely the area in which Uncanniness operates, just on the border of normalcy but with something not quite right. That’s essentially Jentsch’s definition of the Uncanny—uncertainty—but Freud wants to take it further, and he develops his argument with a close reading of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 1817 short story The Sandman.

The Sandman

Freud picks up on Jentsch’s brief mention of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s stories as a fount of uncanniness to do a deep dive into The Sandman. While Jentsch only briefly alludes to the story, Freud provides an extensive reading of The Sandman and the specific ways it evokes the Uncanny.

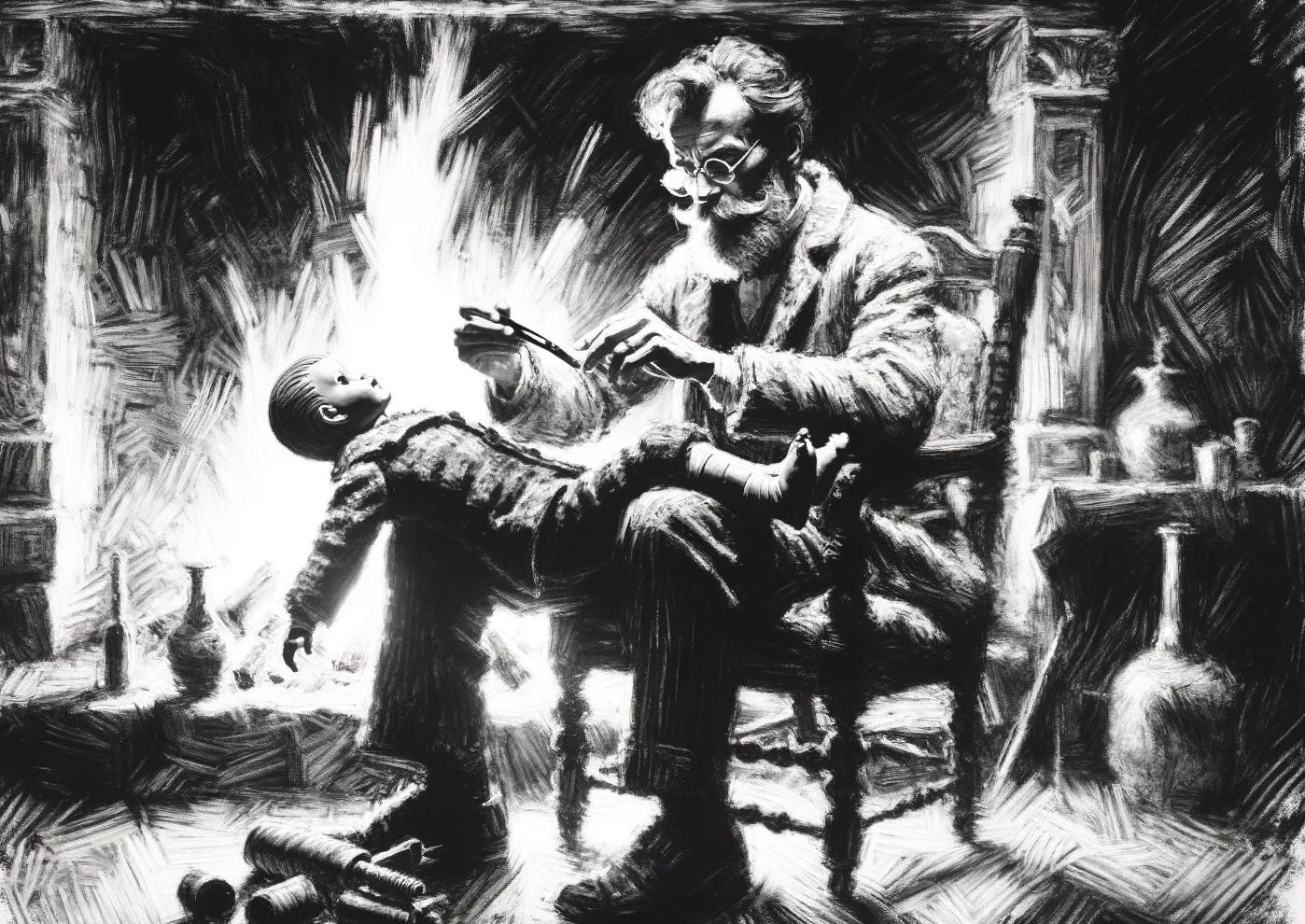

The Sandman is itself a long and fairly complex story that I’ll try to describe in brief. Through an epistolary structure, it follows a young man named Nathanael, who experiences a series of childhood traumas that haunt him throughout his life and eventually lead him to madness. As a young adult up he meets and falls in love with a girl named Olimpia, who turns out to be a human-like automaton. Throughout, Nathanael is haunted by the figure of the Sandman, a boogeyman who steals the eyes of children who won’t sleep, to feed them to his own children on the moon. The Sandman appears across the story in various doppelgänger guises. As a boy, Nathanael comes to associate the Sandman with a colleague of his father, the mysterious lawyer Coppelius. One night Nathanael hides in his father’s room, hoping to see the Sandman, and sees Coppelius performing some kind of alchemy in a fireplace. The climactic section follows:

“He looked like Coppelius, whom I saw brandishing red-hot tongs, which he used to take glowing masses out of the thick smoke; which objects he afterwards hammered. I seemed to catch a glimpse of human faces lying around without any eyes - but with deep holes instead.

'Eyes here' eyes!' roared Coppelius tonelessly. Overcome by the wildest terror, I shrieked out and fell from my hiding place upon the floor. Coppelius seized me and, baring his teeth, bleated out, 'Ah - little wretch - little wretch!' Then he dragged me up and flung me on the hearth, where the fire began to singe my hair. 'Now we have eyes enough - a pretty pair of child's eyes,' he whispered, and, taking some red-hot grains out of the flames with his bare hands, he was about to sprinkle them in my eyes.”

Nathanael’s father manages to save his eyes, but Nathanael is still punished (which I will expand on soon), and shortly after, Nathanael’s father dies in a mysterious accident, seemingly caused by Coppelius. This primal scene in the story forms the foundation of Freud’s first argument about the Uncanny—that the Uncanniness stems from Nathanael’s anxiety around losing his eyes, eyes which can be interpreted as a phallic symbol, and thus connected to castration anxiety and the Oedipus complex. Freud draws this into the idea that the Uncanny can sometimes proceed from repressed infantile complexes, or basically, “the return of the repressed.” This overtly psychoanalytic definition of the Uncanny may be useful for clinical purposes, but I’ll be focusing on Freud’s second definition of the Uncanny, the return of surmounted primitive beliefs:

“Let us take the uncanny in connection with the omnipotence of thoughts, instantaneous wish-fulfillments, secret power to do harm and the return of the dead. The condition under which the feeling of uncanniness arises here is unmistakable. We—or our primitive forefathers—once believed in the possibility of these things and were convinced that they really happened. Nowadays we no longer believe in them, we have surmounted such ways of thought; but we do not feel quite sure of our new set of beliefs, and the old ones still exist within us ready to seize upon any confirmation. As soon as something actually happens in our lives which seems to support the old, discarded beliefs, we get a feeling of the uncanny; and it is as though we were making a judgment something like this: ‘So, after all, it is true that one can kill a person by merely desiring his death!’ or, ‘Then the dead do continue to live and appear before our eyes on the scene of their former activities!’, and so on.

And conversely, he who has completely and finally dispelled animistic beliefs in himself, will be insensible to this type of the uncanny. The most remarkable coincidences of desire and fulfillment, the most mysterious recurrence of similar experiences in a particular place or on a particular date, the most deceptive sights and suspicious noises—none of these things will take him in or raise that kind of fear which can be described as ‘a fear of something uncanny.’ For the whole matter is one of ‘testing reality,’ pure and simple, a question of the material reality of the phenomena.”

The idea works on both a historical and personal level—older societies with belief systems where the boundary between the real and divine was more porous, as well as the development of an individual from the magical thinking of childhood to the rational thinking of adulthood. Unlike his first description of the Uncanny as the return of a specific childhood complex, this surmounted beliefs definition of the Uncanny is about the return of an earlier structure of thought where the basis of reality, and crucially, the self, is called into question.

Freud goes on to develop this theory of the Uncanny with a number of examples, including ghosts, which appear to confirm “the doctrine of spiritual beings”; the double/doppelgänger, which raises questions about the immaterial soul (more on this later); lifelike inanimate objects like dolls, automata, and waxworks; coincidences which appear to validate the idea of fate or destiny; magical powers like the evil eye; and psychical phenomena like telepathy, precognition, and wish fulfillments, which suggest the “omnipotence of thoughts.” But in a strange omission, or perhaps repression, he glosses over one of the most striking images in the Sandman story.

In the aforementioned primal scene, where Nathanael encounters Coppelius by the fire and is caught, Nathanael’s father convinces Coppelius not to pull out his eyes, but he instead inflicts a far stranger punishment:

“Whereupon Coppelius answered with a shrill laugh: 'Well, let the lad have his eyes and do his share of the world's crying, but we will examine the mechanism of his hands and feet.' And then he seized me so roughly that my joints cracked, and screwed off my hands and feet, afterwards putting them back again, one after the other.”

Freud references this moment briefly in a footnote, where he reduces it to another castration equivalent and Nathanael’s infantile attitude towards his father. It’s understandable that he takes this approach, given his desire to shift away the emphasis of Jentsch’s analysis of “uncertainty” towards infantile complexes, but in doing so he misses perhaps the most significant Uncanny moment in the story. This singular image of Nathanael’s hands and feet being “screwed off” like a doll suggests that the source of his madness, and the events that follow in the plot, lie not in his “uncertainty” of Olimpia’s ontological status as a human or automaton, but his own. It is an emblematic example of Freud’s own argument about the return of surmounted primitive beliefs, as well as the anxiety at the heart of the enlightenment—the lingering doubt that earlier beliefs and understandings are completely dead and gone.

This ontological uncertainty is fundamental to Freud’s Uncanny, especially in its connection to death, on which Freud writes:

“There is scarcely any other matter, however, upon which our thoughts and feelings have changed so little since the very earliest times, and in which discarded forms have been so completely preserved under a thin disguise, as that of our relation to death.”

As noted above, nearly all iterations of the Uncanny seem to circle back to the same point: death. To understand the significance of this movement, we will need to take a detour to another of Freud’s central concepts, the Death Drive.

The Death Drive

The Uncanny was written in the midst of the composition of one of Freud’s other essential texts, Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), and there’s considerable overlap between the concept of the Uncanny and the development of Freud’s thought on the Death Drive. The main idea of Beyond the Pleasure Principle is that humans are driven by two principles: Eros, aka the Pleasure Principle, the affirmative drive towards survival, pleasure, sex, creativity, etc. and its opposition, the Death Drive, the destructive drive towards self-annihilation. The two are in constant battle because of their underlying similarity—the Pleasure Principle is about the relief of tension, resulting in the pleasure of relief. The Death Drive is also about the relief of tension, but in the opposite direction—the relief of being alive—resulting in compulsive behavior, and is frequently associated with repetition, aggression, and self-destruction. The Death Drive is the desire to return to the state of non-existence which preceded biological life, as Freud describes, it is “an urge in organic life to restore an earlier state of things.”

Because the two pieces were written at the same time, the Uncanny is conceptually proximate to the Death Drive, made explicit by Freud in a footnote where he cites Beyond the Pleasure Principle and recommends it to readers interested in learning more about drives. Immediately after, he outlines the connection between the Uncanny and the Death Drive:

“It must be explained that we are able to postulate the principle of a repetition-compulsion in the unconscious mind, based upon instinctual activity and probably inherent in the very nature of the instincts—a principle powerful enough to overrule the pleasure-principle, lending to certain aspects of the mind their daemonic character, and still very clearly expressed in the tendencies of small children; a principle, too, which is responsible for a part of the course taken by the analyses of neurotic patients. Taken in all, the foregoing prepares us for the discovery that whatever reminds us of this inner repetition-compulsion is perceived as uncanny.”

So it could be said that one source of the Uncanny is things that remind us of our inner repetition-compulsion, from the Death Drive. Freud notes the uncanniness of repetitions in various forms:

“For instance, we of course attach no importance to the event when we give up a coat and get a cloakroom ticket with the number, say, 62; or when we find that our cabin on board ship is numbered 62. But the impression is altered if two such events, each in itself indifferent, happen close together, if we come across the number 62 several times in a single day, or if we begin to notice that everything which has a number—addresses, hotel-rooms, compartments in railway-trains— always has the same one, or one which at least contains the same figures.”

The Double

The repetition in the Uncanny takes on a human form in the concept of the Double, or doppelgänger. Freud draws from Otto Rank’s literary analysis of the Double, although looking ahead to Lacan can also deepen our understanding of the relevance of the Double. In his excellent analysis of the Uncanny and Lacan, I Will be With You on Your Wedding Night, Mladen Dolar writes:

“For all of them the shadow and the mirror image are the obvious analogues of the body, its immaterial doubles, and thus the best means to represent the soul. The shadow and the mirror image survive the body due to their immateriality—so it is that reflections constitute our essential selves.' The image is more fundamental than its owner: it institutes his substance, his essential being, his ‘soul’; it is his most valuable part; it makes him a human being. It is his immortal part, his protection against death.”

The Double, an eerie duplicate of oneself, appears as one does in a mirror, which Dolar connects to the mirror stage of development. Lacan describes the mirror stage, the recognition of the self as an imaginary figure, as the moment where one is split from their immediate childhood state of wholeness, of jouissance, and becomes aware of themselves as an autonomous being. In other words, the moment of castration, the constitution of the subject and their entry into language, from the Real into the Imaginary.

'“It is only by virtue of one's mirror reflection that one can become endowed with an ego, establish oneself as an ‘I.’ My ‘ego- identity’ comes from my double.”

The difference between looking in the mirror in real life, and the literary/Uncanny concept of the Double is that the Double exists in the world, can go off and commit acts that the original would never dare to commit, enacting the jouissance that they lost when first going through the mirror stage.

“We can now see the trouble with the double: the double is that mirror image in which the object a is included. So the imaginary starts to coincide with the real, provoking a shattering anxiety. The double is the same as me plus the object a, that invisible part of being added to my image.”

The Double, filtered through Lacan, presents an interesting picture of Uncanniness not as a lack, an almost-human lacking some human characteristic, but as something overflowing with too much human, more than human: human+object a, with object a being the Real, the original lack that was constituted when the whole infant recognizes itself in the mirror and is thus split and brought into the world of language as a subject. The Double therefore represents an impossible synthesis of the Real and the Imaginary.

Here we can begin to bring together some disparate points that have been floating around. The Double is Uncanny because it ultimately reminds one of the Real—of the reality that remains out of reach once one has been born into language—which subsequently reminds one of death, our ego, the awareness of our limited subjecthood existing within a symbolic order.

“One could say that the double inaugurates the dimension of the real precisely as the protection against ‘real’ death. It introduces the death drive, that is, the drive in its fundamental sense, as a defense against biological death. The double is the initial repetition, the first repetition of the same, but also that which keeps repeating itself…”

The Double embodies the core characteristics of the Uncanny—ontological uncertainty, the return of primitive beliefs, the repetition of the Death Drive—flashes of the Real erupting into the Imaginary. And when we think of certain long-gestating concepts like the singularity, human-AI immortality, simulation via Matrix-like computer/brain interfaces—the Double as repetitive defense against biological death comes into focus as a foundation of the modern Uncanny.

The Uncanny Valley and AI Images

Having developed a theory of the Uncanny rooted in psychoanalysis, we can now take a look at how these concepts apply specifically to The Uncanny Valley. On a basic level, lifeless objects—a prosthetic hand, a CGI character, an AI-generated image—are imbued with the illusion of life, undercut only by some difficult-to-quantify strangeness.

But not all Uncanniness is created equal. I would suggest that the first order of the Uncanny of AI generated images came from their content—like the above early viral GAN image, where everything looks almost familiar but you can’t quite identify anything—it seems to short circuit the pattern-recognizing parts of our brain. Acting on a similar level is the long period when AI image generators had difficulty rendering hands (also notable for the centrality of prosthetic hands in Mori’s essay). The tell-tale mangled hands (perhaps AI parapraxes) become the Uncanny signifier. In both of these examples, something in the pictures themselves tips us off to their Uncanniness.

But the second order is an Uncanny form—where the AI images are actually indistinguishable from “real” images. The medium becomes the message—within the first order, the images are the medium that delivers Uncanniness through their strange content. In the second order, the medium is the internet, social networks, media channels—and the Uncanniness is delivered through the form of perfectly convincing “fake” images.

I witnessed this recently when someone Tweeted some images of monks playing synths in the mountains. They look pretty good, but I could immediately tell they were AI-generated, having seen a lot of these sorts of images. The person who posted it was called out, but insisted they wouldn’t post it if it was AI, and that as far as they knew it wasn’t, showing an online tool that claimed it was likely not AI-generated. They changed their original reply to the above, acknowledging that they were fooled.

This scenario was more Uncanny to me than an AI image of someone with weird hands—the reminder that what it means to create, to relate, to validate, is undergoing a colossal shift, provoking anxiety about that future, and even moreso, a retroactive anxiety that what was thought to be most fundamental to the human soul could be recreated with lines of code (or the turning of gears, the strings of puppets, the shutter of a camera).

This may be why some artists have become the most vocal opponents of AI—because their specific background positions them to viscerally understand the uncanny form of AI. Artists spend massive amounts of time honing their unique abilities, and it inevitably becomes a part of their ego and self-identity. When an image model recreates and regurgitates artworks in their style in seconds, it is not only upsetting for the logical, practical, job-related reasons, but also because of the existential uncertainty it provokes. An AI forgery appears like a Double in their own image, the real bubbling up from the digital black box. Beyond “will this thing take my job,” the more disturbing question it provokes is, “am I any different from it?”

Put another way, think about the immortal quote from Syndrome: “When everyone’s super, no one will be,” but replace ‘super’ with ‘human.’

The Future of the Uncanny

The Uncanny moves through the dialectical opposition of heimleich/unheimleich, and its form is appropriately one of constant oscillation, whose waves continue to equally enthrall and unsettle us. As demonstrated by the figure of Olimpia in The Sandman, the questions raised by lifelike human automata have been confounding us for centuries. But the real Uncanny encounter is not taking place between the reader and Olimpia, as Jentsch would suggest, nor Nathanael and his father, as Freud would suggest; but between Hoffmann and the reader. In the primal scene of Nathanael’s hands and feet being rearranged, Hoffman’s puppet-show of a novel confronts us with the suggestion that it is not Olimpia who is the real automaton but Nathanael, and by extension, ourselves.

Similarly, the Uncanny Valley’s source of anxiety is not simply robots that look lifelike, with some deadness behind the eyes—because we see them as our Double, as an overdetermined Uncanny nexus point of repetition, automation, omnipotence of thought, wish fulfillment, and jouissance—and thus realize that we ourselves are lifelike with some deadness behind the eyes. As Lacan says, the ego is constructed like an onion with no center, just a succession of peeling identifications. Like the dotted line on Mori’s second chart that travels backwards from human to corpse, we are standing on the cliff’s edge of the Uncanny Valley, confronted with our own lifeless reflection.

As AI and LLMs perform more-human-like tasks with ever more efficiency, we can see the double movement held in the original concept of the Uncanny. As technological advancements continue to shift the emphasis between heimleich/unhemlich, the Uncanny Valley deepens. We are faced not with the fear that the robots are real, but rather, that we are not.