Rabbit Holes

I’ve had a handful of experiences where a chance encounter with a book has radically changed the course of my life, the act of flipping through the pages rerouting my future like the flap of butterfly wings on the other side of the world. Stumbling across William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, a massive postmodern novel of art forgery and fraud in a Portland library, was one of these moments. On a whim I decided to check it out, mostly for the challenge of reading something long and difficult over an uneventful summer. It turned out to be one of the most formative reading experiences I’d ever had, reframing my conception of what a novel could be and do, inspiring me to return to college to finish my degree, and shaping the next decade of the way I made and thought about art. Tracing back the series of branching paths that unravelled from my encounter with The Recognitions, it’s clear that my life would look very different if it hadn’t happened to be on that library shelf that day.

Shortly after finishing my essay on Vilém Flusser and AI, I fell down another rabbit hole of AI-adjacent literature from an unexpected source. While reading through the recent New Yorker article on Ashgar Farhadi’s plagiarism, the word “agape,” defined as “a Greek term for love that persists without the expectation of reciprocation,” caught my eye. Seeing this unusual word in the wild triggered a memory of Gaddis’s final work Agapē Agape, a novella loosely about the invention of the player piano as the origin of art’s move away from authenticity towards mechanized uniformity. It had been sitting on my to-read shelf for years, but its central theme suddenly felt like it might be relevant to the research I’ve been doing, so I finally took the plunge and read it in one sitting.

My intuition turned out to be correct—Agapē Agape is relevant to the AI art conversation, albeit as the antithesis of Flusser’s writing. While Flusser expressed a detached uncertainty about the potential of AI and the internet tinged with an ultimate note of hope, Gaddis’s diagnosis couldn’t be more pessimistic. Their methods are also opposite: Flusser’s theoretical work is ostensibly non-fiction, rooted in history, but veers into the speculative, while Gaddis’s presents as a work of fiction, but is actually the result of decades of research originally intended for a non-fiction text on the history of the player piano.

The History of Agapē Agape

The origins of Agapē Agape go back to 1945, when Gaddis was working as a fact-checker at the New Yorker. He was assigned to edit an article on the player piano, which sent him down his own research rabbit hole, developing into an obsession that would last the rest of his life. Gaddis’s first writing on the player piano was a short non-fiction article published in 1951, the seed of the idea that would crystalize in Agapē Agape nearly 50 years later:

There was a place for everyone in this brave new world, where the player offered an answer to some of America's most persistent wants: the opportunity to participate in something which asked little understanding; the pleasure of creating without work, practice, or the taking of time; and the manifestation of talent where there was none.

The player piano perfectly symbolizes one of Gaddis’s core ideas: the decline of art as a sacred conversation linking the soul and mind of a Great Artist and their audience, and its slide into frivolous entertainment, mere pleasure, reflecting a broader trend in American society towards mechanization and homogeneity, with the reduction of the human element.

It’s the same shift that Flusser describes in less scathing terms—the fall of the era of Great Artists replaced by a mechanically democratized future, elevating communication into a global artistic conversation in which anyone can participate, replacing the rareified pact between special individuals. While Flusser’s book reckons with this shift matter-of-factly, without much of a moral judgment, Gaddis makes no secret of the fact that he finds this mechanization a force of apocalyptic hopelessness, as a powerless observer looking on in despair at the necrotizing foundation of the art he’s devoted his life to. Accordingly, Agapē Agape is his final desperate scream into the void, taking the form of a long unbroken monologue from a terminally ill narrator trying to synthesize decades of scattered research material on the player piano and related subjects into something before he dies. The unnamed narrator is a barely fictionalized avatar for Gaddis—himself suffering from cancer when he assembled the book, similarly brain-fogged from prednisone and surrounded by mountains of disorganized material that he’d gathered over the years.

Rather than the non-fiction form he originally struggled with, the thinly-veiled fictional conceit allows Gaddis to transfigure his research into a work of art itself, making it a terminal example of the distinctive human-centric artworks that he opposes to the mechanizing force embodied by the player piano. He finished the book shortly before his death in 1998, and it was published posthumously in 2002, intended as his final statement.

The All-or-None Machine

Below is the first sentence of the Agapē Agape, in full:

No but you see I’ve got to explain all this because I don’t, we don’t know how much time there is left and I have to work on the, to finish this work of mine while I, why I’ve brought in this whole pile of books notes pages clippings and God knows what, get it all sorted and organized when I get this property divided up and the business and worries that go with it while they keep me here to be cut up and scraped and stapled and cut up again my damn leg look at it, layered with staples like that old suit of Japanese armour in the dining hall feel like I’m being dismantled piece by piece, houses, cottages, stables orchards and all the damn decisions and distractions I’ve got the papers land surveys deeds and all of it right in this heap somewhere, get it cleared up and settled before everything collapses and it’s all swallowed up by lawyers and taxes like everything else because that’s what it’s about, that’s what my work is about, the collapse of everything, of meaning, of values, of art, disorder and dislocation wherever you look, entropy drowning everything in sight, entertainment and technology and every four year old with a computer, everybody his own artist where the whole thing came from, the binary system and the computer where technology came from in the first place, you see?

Gaddis announces up front that the central subject of his work is “the collapse of everything, of meaning, of values, of art.” In other words, “entropy.”

He continues, “entertainment and technology and every four year old with a computer, everybody his own artist where the whole thing came from, the binary system and the computer where technology came from in the first place, you see?” Alluding to technology’s infantilization of everyone, Gaddis goes on to situate the origin of entertainment and technology as one and the same, emblematized by the player piano.

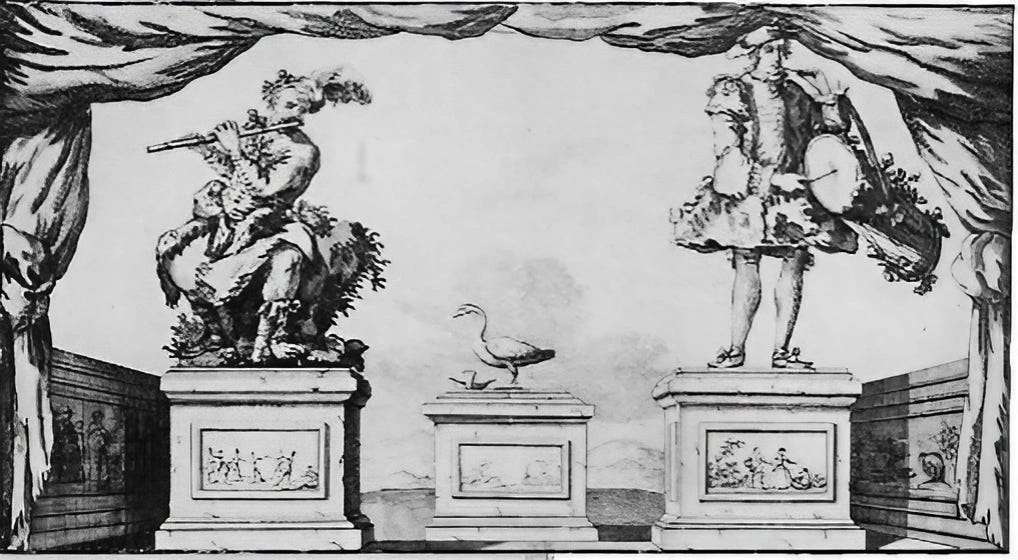

Gaddis venerates the Great Artists of history, who struggle through suffering to deliver something of enduring value and meaning to humanity. Technology, on the other hand, has its origins in parlor tricks, toys, the tinkering of scientists and inventors that results, at its most innocuous, in amusement, and at worst, in the dehumanization of the entire population. The key distinction can be located in the binary system, “the all-or-none machine,” which allows for only two outcomes, on or off, with none of the shades of grey in human decision-making. He associatively traces its origins from Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine, a calculator credited as the first mechanical computer in the 1820s, back to Joseph Marie Jacquard’s loom, a mechanized textile machine patented in 1804, itself a refined version of the first automated loom invented by Jacques de Vaucanson in 1745. Vaucanson’s loom was powered by a system of punch cards he had first used in his 1734 invention “The Flute Player,” a life-sized automata that played the flute, via a rotating drum pierced with holes diverting the airflow—the predecessor to the binary system.

“It’s the same principle Vaucanson used for his flutist, this drum pierced with holes and levers controlling its fingers and lip and tongue movements the air supply driven through the lips against the edge of the holes in the flute it was actually playing the notes selected by the holes in the drum, the notes selected by the holes in that roll of paper because the piano was the epidemic, it was the plague spreading across America a hundred years ago with its punched paper roll at the heart of the whole thing, of the frenzy of invention and mechanization and democracy and how to have art without the artist and automation, cybernetics you can see where the, damn!”

When Vaucanson presented The Flute Player at the Academie d’Sciences, it drew outrage from Johann Joachim Quantz, an accomplished flutist, for its “shrill tone.” So in some sense, the origins of the digital world we live in now, the underlying structure of our incredibly sophisticated big data AI models, emerges from a toy, a lifeless robot poorly simulating the act of artistic performance. Maybe the AI then, rather than bringing us into a brave new world, has actually brought us full-circle, closing the binary loop that opened some 300 years ago. That’s certainly how Gaddis would see it if he were alive today. This historical context is established in the early pages of Agapē Agape, and while the piano does continue to reappear throughout the text, Gaddis focuses next on existential consequences for art that the player piano represents.

Homo Ludens in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

After tracing the history of the player piano, Gaddis stages an extended hypothetical dialogue between two titans of cultural history, John Huizinga and Walter Benjamin. Huizinga’s most famous work, Homo Ludens (also referenced by Flusser) suggests that play is a necessary condition of generating culture, and that in the 18th century the rise of art corresponded to the decline of religion; Benjamin’s most famous work, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, discusses, among other things, the way in which mechanical reproduction devalues the “aura” of an authentic original artwork, and shifts the social value of art form the private sphere of elite collectors to the public sphere of galleries and museums. The form of this conversation floats associatively between the authors’ voices, a back-and-forth of the major points of their work.

“God knows what it takes anyway my head’s splitting, falls right into line doesn’t it, collapse of authenticity collapse of religion collapse of values what Huizinga called one of the most important phases in the history of civilization, and Walter Benjamin picks it up in his Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in the heap somewhere, the authentic work of art is based in ritual he says, and wait Mr. Benjamin, got to get in there the romantic mid-eighteenth century aesthetic pleasure in the worship of art was the privilege of the few. I was saying, Mr. Huizinga, that the authentic work of art had its base in ritual, and mass reproduction freed it from this parasitical dependence. Ah, quite so Mr. Benjamin quite so, turn of the century religion was losing its steam and art came in as its substitute would you say? Absolutely Mr. Huizinga, and I’d add that this massive technical reproduction of works of art could be manipulated, changed the way the masses looked at art and manipulated them. Inadvertently Mr. Benjamin, you might say that art now became public property, for the simply educated Mona Lisa and the Last Supper became calendar art to hang over the kitchen sink. Absolutely Mr. Huizinga, Paul Valéry saw it coming, visual and auditory images brought into homes from far away like water gas and electricity and finally, God help us all, the television. Positively Mr. Benjamin, with mechanization, advertising artworks made directly for a market what America’s all about. Always has been, Mr. Huizinga, Always has been, Mr. Benjamin. Everything becomes an item of commerce and the market names the price. And the price becomes the criterion for everything. Absolutely Mr. Huizinga! Authenticity’s wiped out when the uniqueness of every reality is overcome by the acceptance of its reproduction, so art is designed for its reproducability. Give them the choice, Mr. Benjamin, and the mass will always choose the fake. Choose the fake, Mr. Huizinga! Authenticity’s wiped out, it’s wiped out Mr. Benjamin. Wiped out, Mr. Huizinga. Choose the fake, Mr. Benjamin.”

Following this exchange, Gaddis includes a bit about Dolly the sheep, the first successful mammal clone (which occurred in 1996, two years before Gaddis completed Agapē Agape), leading into a passage that gets to the core of the implications of what is lost in this new universe of imitation:

“I’ve got to write this down before it’s lost, before it’s stolen, just to get the sequence right, what follows what, post hoc ergo this game you can’t win because that’s not why you play it trying to cultivate this whole swamp of chaos and chance, of paradox and perversity to wipe out the whole idea of cause and effect and, and, get my breath before i lose the, these belly-talkers and detached selves bred and cloned to be reproduced because that’s the heart of it, where the individual is lost, the unique is lost, where authenticity is lost not just authenticity but the whole concept of authenticity, that love for the beautiful before it’s created that that, it was Chesterton wasn’t it? that natural merging of created life in this creation in love that transcends it, a celebration of the love that created it they called agapē, that love feast in the early church, yes. That’s what’s lost, what you don’t find in these products of the imitative arts that are made for reproduction on a grand scale got to find some paper, piece of blank paper i’ve finally got the pencil now, now.”

What is lost is not just authenticity, but the concept of authenticity, of love—agapē—God’s love, love without reciprocation, a deep and profound sacrificial love. Agapē has been torn wide open, agape. In passages like this, the sincerity beneath Gaddis’s bitterness and nihilism and irony shines through. Those prickly layers of postmodern armor are a defense mechanism against the tenderness of the loss at the heart of his work, the loss of love. His intensity of feeling for this loss accounts for the seriousness with which he rails against it, the engine that drove his desire to continue to make art, even throughout a life where his talents were mostly under recognized and underappreciated.

Imitation of Life: Phantom Hands

It’s sensible that Gaddis, who started his career with a novel on art forgery, and ended it with a treatise on the player piano’s fabrication of artistic creation, speaks to the current conversation on AI-generated art. As AI art’s fidelity improves, its ability to mimic artists’ styles getting better and better, it marches closer to the fulfillment of his worst fears. Here the narrator quotes from advertisements on piano rolls:

“Here’s one, here’s what they wanted. ‘you can play better by roll than many who played by hand' you see? ‘and you can play all pieces while they can play but a few. and now even untrained persons can do it,’ breaks your heart.”

Sounds familiar. He goes on to describe the “piano player” that came before the player piano, an automata in the vein of Vaucanson’s flute player, that was advertised as being able to simulate the great masters, like Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, and Chopin.

“Here’s Debussy and Grieg giving a testimonial. ‘Many of the artists will never play again, but the phantom hands will live forever’ there that’s what it’s about, no more wooden fingers but phantom hands.”

Phantom hands becomes a recurring phrase, representing the trace of the performer whose work is being mechanically reproduced—the ghost of the artist as a living vital phenomenon resurrected, through binary necromancy, as entertainment.

“where did it go from participating even in these cockeyed embraces with Beethoven and Wagner and, and Hofmann and Grieg and these ghostly hands on the, what took it from entertaining to being entertained? From this phantom entertainer to this bleary stupefied pleasure seeking, what breaks your heart.”

AI is the ultimate set of phantom hands, the master of simulation that takes it beyond what Gaddis could have imagined. Not only can they play an existing song in the style of a master, but they can apply the master’s style to entirely new songs. All art is curation, yes but AI is trained on the collected images of human art history, an endless pool of influences to draw from that expands far beyond the limits of a single human memory. While this infinity of influences means that the AI can easily make new images that could have never been imagined previously, it’s far more common that AI artists default to well-trodden paths. It’s common practice that adding “in the style of [X artist]” will give images the patina of a canonical artist, living or dead, and there’s a shortlist of artists or styles that many AI artists draw from (Greg Rutowski, Moebius, HR Giger, trending on artstation, 8K unreal engine, etc). More directly related to the music metaphor, there are also dynamic performance models based around the human voice, like Holly Herndon’s Holly+, which will soon make any artist’s voice available for everyone to try on. As an inevitable result of its datasets source in the cumulative fruits of humanity’s labor, the ultimate job of AI is imitation.

But on some level, isn’t all art imitation? In the previous essay, I defined curation as the defining act in artmaking, and curation is all about synthesizing received influences, the same thing that humans and AI both do. And for all his blustering about authenticity, Gaddis’s own artistic practice frequently weaves imitation, plagiarism, and mimicry into its fabric, deconstructing the relationship between copy and original. The Recognitions in particular includes extensive unattributed quotes and allusions, everything from advertisements to Flemish art history to medical texts and all types of literature and poetry, the origins of which can be traced page by page on the website The Gaddis Annotations. In some ways, his novels could be considered proto-hypertext, collections of overdetermined word clusters pointing outwards to a decentralized bibliography in a thousand other directions. They’re novels of communication, of systems, networks, speaking in the language of their time, holding the realities of 20th century American society that Gaddis loathed up to a funhouse mirror, while simultaneously indulging in aspects of them, interpolating them into the form. This is all to say, he himself was a master of imitation, as a gesture to pay tribute to his influences, draw attention to his themes of mimicry and reproduction, and as a way to participate in the global dialogue of art.

Networks of Meaning

So much of aesthetic theory focuses on a work’s internal qualities—its form and content, its dialogue or characters or images or colors, structure, composition, style. But equally important is everything external to the work itself, the intertextual dialogues it bridges with art history and history in general—everything outside the boundaries of the frame. Tapping into this layer opens up a channel of infinitely forking paths. You never know when one word, one image, will instigate a decades long quest, or how far it will take you. Being assigned an article on the player piano, finding The Recognitions in the library, reading the word “agape” in an article online… The avenues that open up from chance encounters, weaving through works across time and space, are an essential side effect of engaging with art, and a core aspect of curation.

Ironically for a medium directly conjured from such a vast well of art history, AI art rarely has this contextual quality. Or at least, it’s harder to pinpoint. AI images, encountered across disparate social media channels, mostly feel disembodied from a singular, recognizable creator, or any wider context—creations of phantom hands. This could be attributed to a number of factors: the absence of spatial and temporal grounding, being created and displayed primarily online with few centralized galleries, the lack of an artists’ signature or built-in metadata, artists’ styles being drawn from without rather than within, the sheer volume of images and the speed at which they’re created. More often than not, the type of AI model being used is more recognizable than the style of an individual AI artist. These are all consequences of the emerging phase that AI art is still in, but none of them are inherent, and the potential to cultivate a richer context is not only there, but necessary, if AI art is to evolve beyond a novelty, a mere pair of phantom hands.

Arguably the most recognized and recognizable working figure in AI is Turkish American artist Refik Anadol, who is about to have his first solo exhibition at the MoMA, and the first major AI artwork in the MoMA. The piece emerged from an online collaboration with the MoMA last year, and is based on AI trained with over 138,000 images from the MoMA’s art archive. Though it’s trained on existing art, the work itself is highly abstracted, leaning into the hallucinatory uncanny quality that AIs can produce. In an interview with the MoMA, Anadol describes the way in which AI machines mirror the human capacity to synthesize influences and memories in a work:

“I think every single location in latent space resonates with how we perceive what happens in our lives. As humans, when we think about how we learn, and recollect our memories, or where our consciousness comes from, we realize that the machine’s process is not so different from our thinking or imagining. And I think machines help us define this powerful feeling of being able to touch and reconstruct memories.”

Anadol’s work is recognizable in part because his aim is not to recreate existing artworks or styles, even when drawing explicitly from one of the richest repositories of Western art. There’s a transfiguration happening, a dialogue with influences rather than just an imitation. When asked about the role of AI artists, he responds:

“For me, art reflects humanity’s capacity for imagination. And if I push my compass to the edge of imagination, I find myself well connected with the machines, with the archives, with knowledge, and the collective memories of humanity. So, like many creators, artists, designers, I feel like I am trying to find ways to connect memories with the future. And it’s not too hard to imagine, for example, that this specific data universe is the entire representation of every single data point that ever existed in the MoMA archive. And they’re all connected, based on their similarities, by the most cutting-edge, recent algorithms.”

This answer resonates with a forward-looking approach to AI, where the source of the AI’s data is a means to make something new, rather than towards simply recreating the past. Even as the publicly accessible models veer closer and closer to coherence and photorealism, the most successful AI art will likely be the pieces that draw out the more distinctive and uncanny qualities specific to the medium. With Anadol’s work soon to be on display at the MoMA, we’re clearly at a turning point for the canonization and distribution of AI art. It’s still uncertain how this will translate to other AI artists, and how future AI art will be cataloged, distributed, and valued.

Art Against the Algorithm

Gaddis’s career fixated on a body of themes that reached their apex in Agapē Agape, at the turn of the millennium. The despair he felt at the devaluation of art in favor of mindless disposable entertainment, or “content,” is easy to feel today, when those forces have only continued to accelerate exponentially. In the face of such a bleak situation, the question emerges: why is art still worth making? Filled with so much negativity, why did Gaddis himself continue to create? The work itself is the answer. It still matters. And it matters more than ever that we take seriously the idea of making art, that the elevation of anyone to the status of artist doesn’t mean the demotion of all art to “content” churned through the all-or-none machine, lost in a sea of indistinguishable data.

Despite his fight against technology, Gaddis’s intertextual approach validates that, on some level, art is data—nodes in a decentralized thought network created through dialogue over the course of thousands of years of history. We can acknowledge this lens, but at the same time, believe that encounters with art can be meaningful in a way that can’t be reduced to a mere exchange of information, and that there is still a case for humans over algorithms. With the proper effort from both artists and engineers, AI art can continue to push art history forward rather than becoming a closed loop of nostalgia, like a player piano roll on endless repeat. As long as there are humans, there will be a place for art, for agapē, for the feeling of discovery when you stumble across something that someone made and released—against all odds—and it opens up another world.