Disclaimer to subscribers: I’m working on another essay on AI art, but the release of the new Sight & Sound poll inspired me to publish this piece on film, as explained below. If you only want to read about AI, there will be more to come soon, but if you’re interested in film, read on.

The Greatest Films of All Time 2022

The new Sight & Sound “Greatest Films of All Time” poll came out yesterday, the once-a-decade list that amalgamates votes from global film critics (and separately, directors) in an attempt to capture the pulse of the film world. There’s a lot to be said about the lists, and I’m sure they will inspire plenty of dialogue, especially as the individual contributors’ lists roll out. But I’m not looking to delve into the gritty details of the picks; instead, I’d like to use the list as a jumping-off point into a larger discussion around canonization. Shortly after the Sight & Sound Poll was released, I saw tweets from Criterion and Janus celebrating that more than 60 of the Sight & Sound films are in the Criterion Collection, and 48 are distributed by Janus (the theatrical distributor symbiotically connected to Criterion). This rather striking fact prompted me to return to an essay I wrote for a film magazine in college, back in 2017, about the role of film distribution as the bottom line shaping film canons, and decided to revisit it.

Five years ago, the film landscape was in transition from the primacy of physical media to the ubiquity of streaming, and I was writing very much in the midst of this shift, focusing mainly on Criterion Collection DVDs/blu-rays, with only a passing mention of the growing spectre of streaming. But many of the trends I was picking up on have proven more relevant as time has gone on. I also happened to spend much of the essay on the films of Jean-Luc Godard, which takes on a new significance with his recent passing, and the way his body of work is being memorialized retrospectively. Considering these events, I’ve decided to release a revised version of the essay here, mostly intact but with some additions and omissions in light of recent history.

Cinephilia™

Most “cinephiles,”1 people who consider themselves film lovers to the point where they make it a part of their identity, have likely entertained, or even cherished, the idea that they have “good taste.” Movie watching is inherently a passive activity, so there has to be some countervalent active process to distinguish oneself among the crowd, and that action happens to be the internal cultivation of taste. The concept of taste, multifaceted and nuanced in its own way, ultimately comes down to selectivity. Broadly speaking, one watches and enjoys certain movies, which they sort into the category of “good movies,” and ignores or dislikes others, which they categorize as “bad movies.” Over a long period of time, this selection pattern forms the basis of any individual cinephile’s taste, which they may then wear as a badge of honor, a testament of their own individuality and uniqueness as a shrewd and intelligent film-watcher. “Good taste” becomes an essential tool for engaging in conversation with other cinephiles about which films they choose to watch, which ones they value or reject, or which directors they like and dislike; the kinds of conversations that film people live for and everyone within earshot finds insufferable.

There are endless social dimensions to taste to be explored—like the ways in which taste is constructed along gender, class, and race lines, and how it changes over time. For my purposes, I’d like to hone in on a particular kind of internet cinephilia, that you might find on Letterboxd, Twitter, Reddit, or other online communities, frequently (though not always) driven by young men. There’s familiar landmarks that can be recognized in a certain type, and certain stage, of cinephilia: the fetishization and brandification of auteur directors, the currency of obscurity, the limiting of discourse into name-dropping or one-upping. In real life, social conventions might stifle these impulses a bit, but on the unaffected public square of the internet, they often run wild. This phenomenon is somewhat understandable considering that the activity cinephilia is centered around is so inherently consumptive. Within a passive hobby where nothing is directly produced, taste becomes the primary measure of any individual participant’s authority—the cinephile’s action is selection, which becomes the bottom line of identity formation. And because streaming means that watching movies is no longer bound to specific times and locations in the real world, there’s boundless opportunity for online film watching and discussion.

My attempt here has been to illuminate a particular narrative around how taste is understood and enacted within cinephile circles. But this framing of individual taste as the driving factor of cinephilia obscures a more materialist question—the question of where the selection comes from in the first place. The personal locus of “good taste” perpetuates an individualist idea of agency, which belies the external, institutional factors that ultimately shape taste. Though there are numerous complex reasons people may gravitate towards certain films more than others, the underlying factor for every film-watcher’s viewing habits is availability. To like and dislike films, one must be aware of them, and be able to see them. And this problem leads to the questions that this essay will actually be dealing with, namely: how are notions of “good taste” formed, and what underlying factors influence the process?

The Canonical Loop

Film canons are one of the strongest influences on viewing habits in classrooms, theaters, and at home, forming both the base and superstructure of availability. Film canons exist in many forms, but the most prominent examples are the lists of “The Greatest Films of All Time,” most famously by Sight & Sound and AFI. These expansive lists can, and often do, provide a starting point for any aspiring cinephile. Usually topped by Citizen Kane, Vertigo, Tokyo Story, and other “unimpeachable masterpieces,”2 these lists can open any young filmgoer’s eyes to a dazzling world of movie magic, and set the precedent for their own personal lists of favorites, providing a compass for future explorations. But the general similarity of the “Greatest of All Time” lists speaks to the self-perpetuating quality of the film canon. The “Greatest Films of All Time” will be re-watched, remain in circulation, and provoke critical conversations over the course of generations, even as contemporary developments in film shift under our feet. It’s a feedback loop, a closed circuit that has largely sustained itself for decades with only minor changes. And the gatekeepers (critics, artists, academics) who shape these lists with their “good taste” in turn shape the “good taste” of the viewing public, some of whom go on to be gatekeepers themselves and reinforce the cycle.

The consequences of this model—critical gatekeepers choosing which films to enshrine in canons to be consumed and internalized by the next generation of gatekeepers—results in a limiting of the films that people watch, and a shift of the agency of “good taste,” from viewers to gatekeepers. But in fact, the agency lies beyond the gatekeepers. Because in order for a film to be slotted into the category of “good movie” in the first place, it has to be seen. The true locus of power, then, is in the higher echelons of distribution, where decisions are often made with predominantly economic motivations.

Depending on its distribution, any film may be seen by a few or a lot of people; if it fails to reach an interested audience, it may toil in obscurity indefinitely, waiting for the day when it might be rescued and re-entered into circulation in the public consciousness. There are many such cases of films that failed to reach an audience on initial release, but have since become canonized classics, and metropolitan repertory film scenes notoriously have the power to shift the critical perception of films over time. Especially in the pre-digital era, the materiality of film reels ensured that a specific film had to be shown at a specific place at a specific time; if the right gatekeeper never saw a certain film, it may never be seen again. Same goes if gatekeepers saw a particular film and, for whatever reason, didn’t like it enough to champion it. No matter how intuitive one’s “good taste” may seem, it is inseparably contingent on whatever films one has seen throughout their life, which (until recently, at least) was contingent on film distributors and circumstance.

The Criterion Effect

Of course, modes of distribution have changed drastically over time, and viewing habits along with them. The most significant shift in the business of film distribution, until the advent of online streaming, was the rise of home video, giving viewers a new level of agency over what films they watch, and when and how they watch them. And no company better epitomizes the canonizing power of home video than the Criterion Collection, which specializes in “important classic and contemporary films” marketed to savvy cinephiles who are willing to pay premium prices for the company’s extensive releases.

Over the years, the quality of Criterion’s library and enduring popularity among cinephiles has made their brand a de facto canon in and of itself. Once a film is consecrated in the prestigious company of Criterion’s numbered spines (counting among their ranks classics from the silent era until now) it has entered into a canon that guarantees an audience of critics and casual fans alike. Criterion, often described as “film school in a box,” is positioned as a beacon of “good taste,” which hungry audiences are happy to bask in and absorb the benefits. Like Penguin Books, A24, or the Sight & Sound list, Criterion is above all a brand, that brings with it an expectation of quality, in both the films and the surrounding packaging—elegantly designed products that make perfect coffee table accessories.

It’s telling that Criterion “haul” videos have become an entire Youtube subgenre, a cottage industry, usually consisting of midwestern teens sifting through the shelves of a Barnes & Noble, gathering stacks of Blu-rays while they narrate their opinions on the films, like a funhouse mirror version of the Criterion closet videos. There’s something a little charming about it, but it’s also off-putting—the ultimate reduction of a transcendent, emotional relationship with an ephemeral artwork, into pure commodity fetishism.

On a base level, Criterion’s success is understandable and well-deserved. They’re good gatekeepers, doing laudable work restoring classic films and bringing lesser-known films to a wider audience. Their library is strong, despite some inevitable biases and blind spots. And their brand now extends into the digital age—after a few fledgling forays into streaming (Hulu, Filmstruck), their service The Criterion Channel, launched in 2019, has finally become a worthy home to their library, matching or even exceeding the quality of their physical releases with excellent programming and a wealth of supplements.

But, for all the good they’ve done, Criterion isn’t immune to the material forces of the world. They are, after all, a company—and a company must make a profit at the end of the day. Profit demands an audience; Criterion has to release movies that, theoretically, somebody will want to see—and hopefully enough people for Criterion to make their money back. They generally navigate this push and pull between crowd-pleasers and more obscure fare successfully. For every Breakfast Club or Wes Anderson release, there’s a Shoah or Stan Brakhage box set. But the correlation between accessibility (in terms of distribution) and accessibility (in terms of a film’s perceived challenge or difficulty to a broad audience) is not always so straightforward. Take, for example, Jean-Luc Godard.

Godard’s Long New Wave

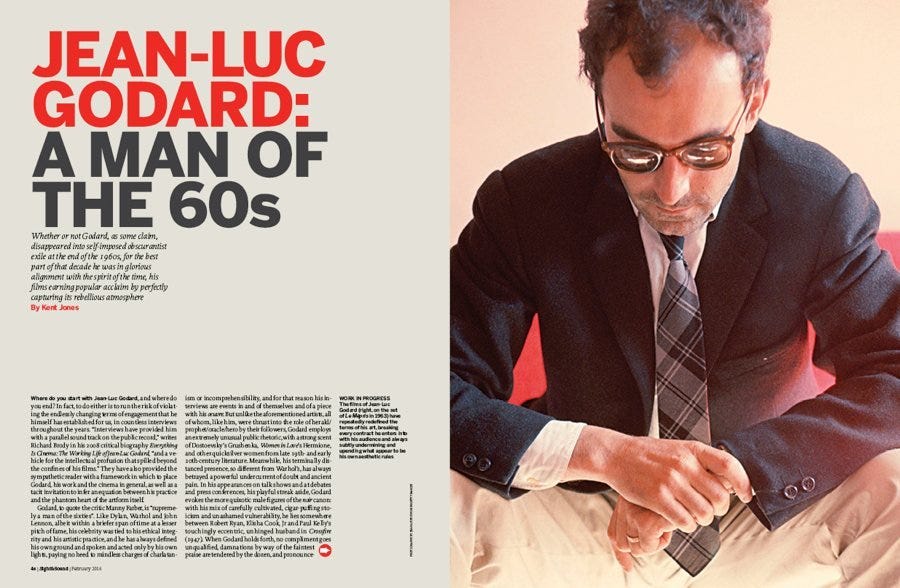

The popular image of Godard is as the 1960s critic-turned-filmmaker enfant terrible poster child of the French New Wave, and in the wake of his recent death, it appears to be the image that will forever be immortalized in the public consciousness. As the familiar narrative goes, Godard’s New Wave streak blew open the formal possibilities of film and left the landscape forever changed. His early run from 1960-67, Breathless to Weekend, scrambled the tropes of American filmmaking in a postmodern blender, creating a fun and free-wheeling body of work that would go on to influence everyone from the New Hollywood filmmakers to Quentin Tarantino and Wong Kar-wai. The reverberations of the New Wave à la Godard persist even today—every year or two there’s sure to be a new indie film that references the New Wave era implicitly or explicitly. Criterion has nearly all of Godard’s New Wave films in their library, ensuring the canonization and enduring popularity of his work and status as a Cinema Icon™.

The problem is, Godard’s career continued for over 50 years after the New Wave subsided, and his later work is arguably even more formally radical and politically vital than the celebrated 10-year period that gets all the attention. You’ll only find two post-New Wave films in the Criterion Collection—Tout va bien (currently out-of-print) and Every Man for Himself. The Criterion Channel’s selection is a bit better, adding Film Socialisme, Goodbye to Language, and The Image Book. But these are still barely scratching the surface of his dozens of later-period films.

For a brief—but by no means comprehensive—sampling of the effects that Criterion has had on Godard, I’ll mention some figures drawn from the popular film database Letterboxd. Of the top 20 most-seen Godard movies, 14 are available in the Criterion Collection on DVD or blu-ray, and with an additional 3 on the Criterion Channel. So that’s 17/20 on Criterion. That leaves the remaining three. A Married Woman, one of the best of his New Wave films which wasn’t widely available until a recent blu-ray release by Kino (itself probably the second most prominent boutique home video distributor), sits relatively low on the list at #18—surely if it had been released by Criterion with the others it would sit among his other new wave hits. Histoire(s) du cinéma, his masterful, lengthy exploration of the history of 20th century images (included on the recent S&S poll), was completed in 1998 and not released on DVD until 2011, via Olive Films. First Name Carmen (1983) sits at #20 on the list, released by Kino in 2019. The further down the list you go the less accessible the films are—again, both in terms of availability and aesthetically. Some, like King Lear3, don’t even have DVD releases. Of course, part of the problem is the increasingly demanding difficulty of some of Godard’s later work. But even something as watchable, and essential, as the Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto-starring Le Gai Savoir (1969) sits low on the list, at #33, as it was largely unavailable until Kino’s 2017 blu-ray release (and now on the Criterion Channel). So it can’t be said that his later films are underseen because they’re too “difficult”—the patterns all leads back to how easy the films have been to see.

All of this is to say that availability has played a substantial role in the public’s perception of Godard and his films. And it’s an issue that bleeds from reception into production. How would the film landscape of today be different if more filmmakers were influenced by Wind from the East or Six Foix Deux instead of Breathless and Band of Outsiders? And what future films are we missing out on by the continued obscurity of Godard’s most vital films? The work that late Godard does towards deconstructing the grammar of film images could push the discourse of cinema ahead ten years if impressionable filmmakers got their hands on some of his lesser-known work.4 But for the time being, we may have to settle for the pithy echoes of the French New Wave’s detached “cool.”

It goes without saying that Jean-Luc Godard remains one of the most famous filmmakers of all time, and was a white European man from a wealthy family with a career that anyone would envy. I say this not to diminish his accomplishments, but to acknowledge that, as far as choices of subjects go, I’ve focused on one who occupies a particularly privileged position. I could have just as easily devoted an article to any number of truly overlooked filmmakers, but that would be missing the point. The myopic canonization of a big name like JLG suggests the problem is inescapable: if a filmmaker as prominent as Godard can slip through the cracks, what else we are missing? And why? Godard is just one example of the influence Criterion wields, itself a microcosm of the way that distribution and economics shapes film culture as a whole.

Streaming the Future

The streaming revolution is a complicated issue, on the one hand devaluing the theatrical experience that most cinephiles treasure, but on the other, bringing infinitely more films to a wider audience than previously possible. Compared to the average filmgoer 50 years ago, anyone outside of a major metropolitan area now has access to films that they could have otherwise never been able to see. The internet is the new theater, and it levels out many of the material restrictions that previously limited gatekeeping roles of good taste to denizens of a handful of cities and institutions. This year’s Sight & Sound poll, somewhat controversially, included a fresh batch of internet-based critics, which some feared would disrupt the canon and lead to a diluted mess. These fears were largely unfounded; the list, despite some omissions and inclusions that will certainly be argued over for years to come (just ask Portrait of a Lady on Fire), it mostly resembles previous years. The internet hasn’t caused a tectonic shift in film taste, yet. The old canons still hold sway, perhaps a testament to Criterion’s enduring influence more than anything.

The next Sight & Sound list will be a better indicator of whether the internet and streaming really have the power to meaningfully shift canons in new directions, but in the meantime, we’re still feeling the downstream effects of a cumulative 100+ years of distribution trends. This article is far from exhaustive, and will hopefully be the beginning of a conversation rather than any kind of conclusion. If there’s anything to take away, it’s to continue to question what “taste” really means. Because taste is never purely an act of spontaneous generation, of individual will. It comes from somewhere—somewhere where commerce plays an inevitable role in what is seen and unseen.

“Cinephile” is inherently kind of a cringe word, but nevertheless serves its purpose, and if anything gels nicely with the often cringe hobby of being a cinephile.

This year’s #1, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, throws an interesting wrench into this tradition. I don’t have the space to go into it in detail here, but needless to say it’s the biggest shakeup the number one spot has had in a while.

Speaking of canonization, New Yorker critic Richard Brody declared King Lear the greatest film of all time on his Sight & Sound ballot.

My turn towards Godard was inspired by a conversation between critics Jordan Cronk and Callum Marsh published on Pop Matters, titled ReFramed No.1: Jean-Luc Godard - The Political Years (1968 - 1979). The article was published in 2011; In the years since, little has changed.

I thought this was gonna be like “Criterion has too much Godard” but plot twist, it was actually like “Criterion doesn’t have enough Godard” :OOO